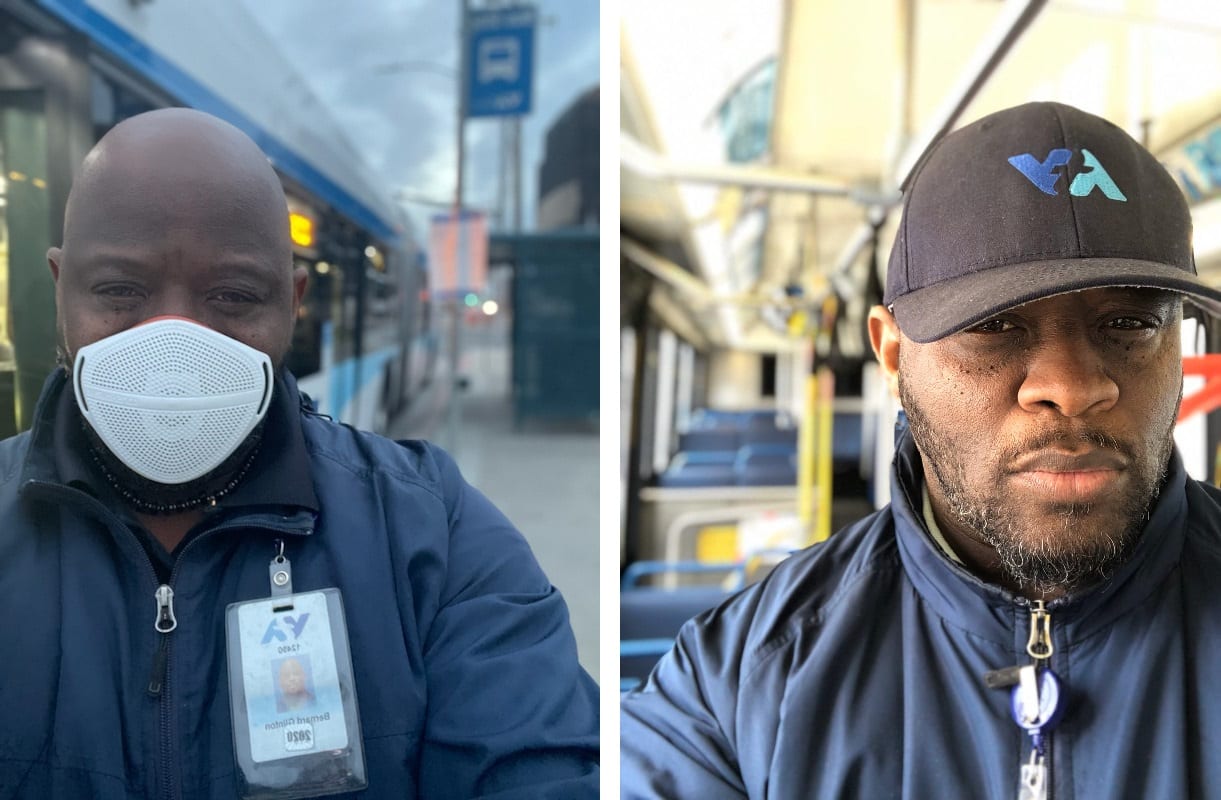

After a long day of driving a transit bus all over Silicon Valley, Bernard Glinton curls up for a night of rest — in his SUV.

The longtime bus driver has slept in his SUV for the last two years to save costs and give himself some much-needed rest.

“There’s tons of people who are commuting because they can’t afford to live in the Bay Area,” said Glinton, who has worked for VTA for a dozen years. “On average, I make $100,000 a year easy … but who wants to give $30,000 a year to someone else for rent?”

Glinton is not alone. In one of the wealthiest regions in the world, public transit workers are sleeping in their cars.

At least 300 workers at VTA live farther than a two-hour drive from San Jose, according to John Courtney, president of Amalgamated Transit Union Local 265. He said many of these workers — bus drivers in particular — choose to sleep in their cars due to the physical distance of affordable areas.

“It becomes a safety issue for bus drivers,” Courtney said. “You can’t be on the road for more than a certain amount of time each day … you’re not getting proper rest.”

Though VTA workers earn above the average pay for similarly-classified employees in the U.S., that money doesn’t go very far in the Bay Area because of the high cost of housing.

Glinton said he used to rent a home in Los Banos, a town about 80 miles away in the Central Valley. Glinton said he spent about $1,000 a month on gas driving back and forth each day and frequently only had time to stop at gas stations for food.

“I seriously just got exhausted from doing that,” Glinton said. That’s when he decided to buy an air mattress for his SUV to sleep on. Glinton eventually began sleeping in the SUV for five days each week.

The savings even allowed him to give money to his ailing mother and improve his credit score.

Mark Nevill also lives in his SUV, which he parks outside the VTA rail yard on Zanker Road in north San Jose.

Nevill has been a VTA employee for 22 years and currently works as a fare inspector. Many more transit workers began sleeping in their cars during the pandemic, he said, particularly as their spouses lost their jobs.

Nevill said he’s been sleeping in his SUV on-and-off for about 15 years, renting rooms in hotels and in homes during the gaps. He’d previously owned a home in Modesto, but fell behind on property tax payments while commuting between five and six hours each day, and eventually sold the home.

“I wasn’t there, because I was always here,” Nevill said. “I was only home one day a week. It wasn’t even worth it.”

Nevill said the first six months living in his car were the hardest.

“You figure out you can’t cook, so you eat out every day — eat a lot of fast food,” Nevill said. “That leads to health problems … it’s not good.”

Both Glinton and Nevill use the showers offered by VTA in their facilities, particularly since gyms have closed during the pandemic. Workers are also welcome to use the microwave and refrigerator in VTA’s breakroom, though employees are now required to eat outside following a new Santa Clara County health order.

Nevill said the showers and parking lots have been available for at least as long as he’s worked there.

“Somebody told me once that VTA said, ‘We will never pay you enough to live in San Jose, so we’re gonna build showers and let you live in the parking lot for free,’” Nevill said.

VTA built the showers at the Cerone bus yard decades ago, according to VTA spokesman Ken Blackstone. Every VTA worksite, including the administration building on North First Street, has showers and locker rooms.

“VTA operators are the second-highest paid in the country, behind San Francisco MUNI,” said Blackstone. “Some VTA employees may choose to permanently live outside of the area where buying a home is more affordable and commute in; some of them may choose to reside in a temporary location until they return home for longer periods.”

The only solution to lowering housing costs and keeping essential workers near their jobs, experts say, is to build more housing — at all income levels.

Local 265 president Courtney said VTA has explored building employee housing in the Alum Rock area of San Jose. However, workforce housing, employee shuttles and other solutions all come with a cost. Nevill said a living wage for him would be closer to $50 an hour, a 43% increase from his current wage of $35 an hour.

“We’re always looking for a cost-of-living allowance,” Courtney said. “But the cost of living is going leaps and bounds above what we can negotiate in a contract.”

After he retires in a few years, Nevill hopes to build a home on some land he’s already bought — in Oklahoma.

“I need $400,000 for where I’m going, but the same house in California would cost $12 million,” Nevill said. “It’s boring out there, but I like boring.”

Contact Sonya Herrera at [email protected] or follow @SMHsoftware on Twitter.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.