San Jose prides itself on progressivism, innovation, inclusion and justice for all. Yet, behind this image lies a quieter contradiction: our continued investment in a carceral system built on the same forced labor that the 13th Amendment never truly abolished.

When voters rejected Proposition 6, which would have ended prison labor in California, we upheld that legacy. Our jails and prisons remain sites of human bondage disguised as rehabilitation.

This pattern didn’t emerge by chance. After the Civil War, Black men were criminalized to replace enslaved labor, a cycle confirmed by new research from the University of Gothenburg. Black people simply walked off the plantation and into a jail cell, a chain gang and prison work camp.

Today, that legacy echoes in places like Santa Clara County, where policies in schools and courts still steer Black children toward cells instead of classrooms. Episode 5 of the Dying to Stay Here podcast focuses on this tragedy in two acts: the school to prison pipeline and the carceral slave trade.

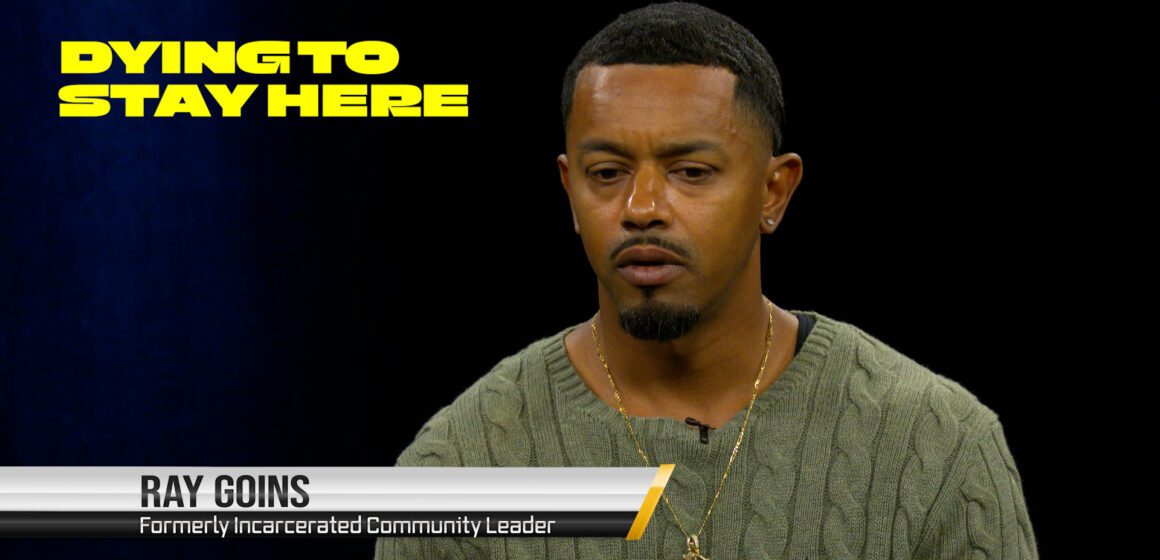

Slavery never ended in America; it was only transformed by the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery unless someone is convicted of a crime. That legacy didn’t skip Silicon Valley. Its echoes appear in our schools, our jails and in the stories of people like Ray Goins. Our jails and prisons became the next stop for forced labor and lost futures. Proposition 6 would have taken the state a step forward, banning forced labor behind bars and offering real pathways to rehabilitation and recovery.

Ray Goins’ life story reveals every fault line in our county’s justice system, beginning with a difficult childhood on the South Side and leading to a hard-won fight for redemption and freedom. Ray’s story, like too many before him and many to follow, doesn’t start in a courtroom or a jail. It begins as a child needing help, a boy asking that someone, anyone, step in before violence at home would set his life on a divergent course.

The system’s answer? Handcuffs on a five-year-old boy, juvenile hall instead of safety. After asking for help, “I never went home again,” said Ray Goins. He bounced around from juvenile hall to foster homes, to group homes and back and forth before landing in a prison cell, all institutions meant to help, too quick to punish, too slow to heal.

For Black children in Santa Clara County, zero-tolerance school policies never fostered opportunity — they shortened the road to incarceration. Here and across the U.S., Black youth are locked up over five times more often than their white peers. These numbers aren’t abstract, they represent shattered childhoods and lost potential. The suspension rate for Black students in Santa Clara County was 6.2% in the 2023-24 school year, significantly higher than the average of 2.2% for all groups, despite Black students comprising only 1.8% of the total enrollment. This overrepresentation is a stark reality for Black students.

In contradiction to our alleged liberal leanings, California continues to lead in some of the worst ways. Contraband watches, shackling, duct-taping and confining men for days on prison floors using confinement and humiliation in the often-failing attempt to find hidden evidence were used 1,200 times in less than three years, but this successfully produced such contraband less than 41% of the time. Only California chains people in isolation cells. One watch lasted 52 days. Convict Raymond Kidd, who said after 13 days on watch at Folsom, “It was the worst two weeks of my life.” Left naked and afraid, bound at his wrists and ankles on a bare concrete floor of a cell.

Despite the odds, Ray Goins forged a new path, lifting himself from survival mode to service. With an ironclad belief in his own dignity, Ray now stands as a community leader, helping some of the very same people he was imprisoned with. His voice rings with both hard truths and hope, a reminder that real change is possible and deserved.

Ray’s outcomes are common. While Black people only represent about 2.2% of Santa Clara County, we are arrested 5.3 times more than whites in the county. The truth of all of this is still brushed aside. Our liberal leanings don’t help us — they quiet us and wrap us in a false sense of security and self-righteousness. As we watch the constant decline in the Black population of our county, we can only say, “It’s no wonder,” with so many children set on this path every year, we have to rethink what justice and opportunity truly mean in our valley.

Ray’s story challenges us not just to bear witness, but to act. Hear his childhood cry, “Someone, please help me.” We can no longer blame Black children for outcomes shaped by a system clearly working against them. Their futures should not be written in chains but forged through opportunity, support, and justice. It’s on all of us — community leaders, policymakers and educators — to heed Ray’s cry for help and break the cycle of incarceration.

Chuck Cantrell is an economist, San Jose planning commissioner and creator of “Dying to Stay Here,” a video and podcast series that explores the entrenched economic and social barriers facing Black communities in Silicon Valley. His columns appear every third Thursday of the month. Contact Chuck at [email protected].

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.