Coronavirus hotspots: Top 3 areas hardest hit in Santa Clara County, Part 1

Albert Camarena sat in a chair on the front lawn of his home in East San Jose, facing eastward toward a vacant elementary school.

“Everybody’s scared,” Camarena said. “They don’t want to be sick.”

Camarena’s neighborhood and its corresponding ZIP code — 95122 — had the highest rate of COVID-19 infections in Santa Clara County as of Nov. 9.

According to county data, 1,988 people tested positive for the virus in 95122. With a population of 57,780 people, the number of cases in the area amounts to a rate of 3,441 cases for every 100,000 people.

This is higher than the average number of cases per 100,000 people in California as a whole, or 2,419, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Camarena works as a mechanic and lives with five other adults in a small house. He said everyone in the neighborhood is trying to adhere to rules and guidelines to slow the spread of the virus, but it’s been difficult.

Camarena has kids but they’re not able to stay at his place due to the risk of catching the virus, so they live with their mother. The father of one of Camarena’s housemates has tested positive for COVID-19.

“I have to protect my kids,” Camarena said.

Overcrowding in low-income neighborhoods in San Jose has contributed to a spike in COVID-19 cases in certain ZIP codes, which also have a large number of minority residents who are essential workers regularly exposed to the virus.

According to available data, the median household income in the 95122 ZIP code is $56,000, less than half of the county’s median household income. The area is also relatively diverse, with roughly equal portions (30%) of residents counted as white, Asian and “other.”

Analilia Garcia, senior manager for Santa Clara County’s Racial & Health Equity office, said the county’s public health department was focused on overcrowding before the spread of COVID-19.

Through its East San Jose PEACE Partnership, a coalition of local and regional organizations aimed at reducing violence and trauma, the county has tried to engage residents and communicate the urgency of the pandemic.

Garcia said there’s a history of mistrust between many East San Jose residents and local government, including public health officials, which the partnership has worked to dispel. Garcia said this work has been crucial to building people’s confidence in the county’s testing and housing infrastructure.

“People are struggling,” Garcia said. “People are trying to better understand what resources and services are available… it’s important that we have trusted messages in the community.”

Santa Clara County Assistant Health Officer Dr. Sarah Rudman said overcrowding due to the housing crisis in the county’s most affected areas is a top concern, exacerbated by the fact that multiple members of a household are working essential jobs that often involve a high rate of interaction with the general public.

“Folks are more likely to be in the service professions in sectors of the economy that have been open the longest,” Rudman said. “It is much harder for folks to separate from each other, and we have seen unfortunate patterns of one person becoming ill in a household and very rapidly the entire household falling ill.”

Rudman said the county’s Isolation and Quarantine Support Team has offered spaces in hotels and motels to people who have been diagnosed or exposed to the virus.

Christine Muangchanh, who lives in a five-bedroom home with nine other people in East San Jose, said the virus and ensuing shutdown order has hit her household particularly hard.

“We’re bottled up in the house. People lost their jobs,” Muangchanh said. “(Those of) us that work, we have to be careful.”

Muangchanh said her elderly grandmother lives with her in the household so she and her other roommates try not to allow unnecessary visitors.

State Assemblymember Ash Kalra, whose district encompasses East San Jose, said the coronavirus pandemic has exposed the region’s stark inequality and society’s reliance on an underserved working class.

“The same neighborhoods that struggle with housing affordability and income inequality, as well as health care access, are struggling the most with COVID,” Kalra said. “Many of the families that live in those neighborhoods are being asked to go to work, so that other families — like my own — can stay home.”

The median price of homes in the ZIP code is $758,623, according to Zillow, rising 15% since last year.

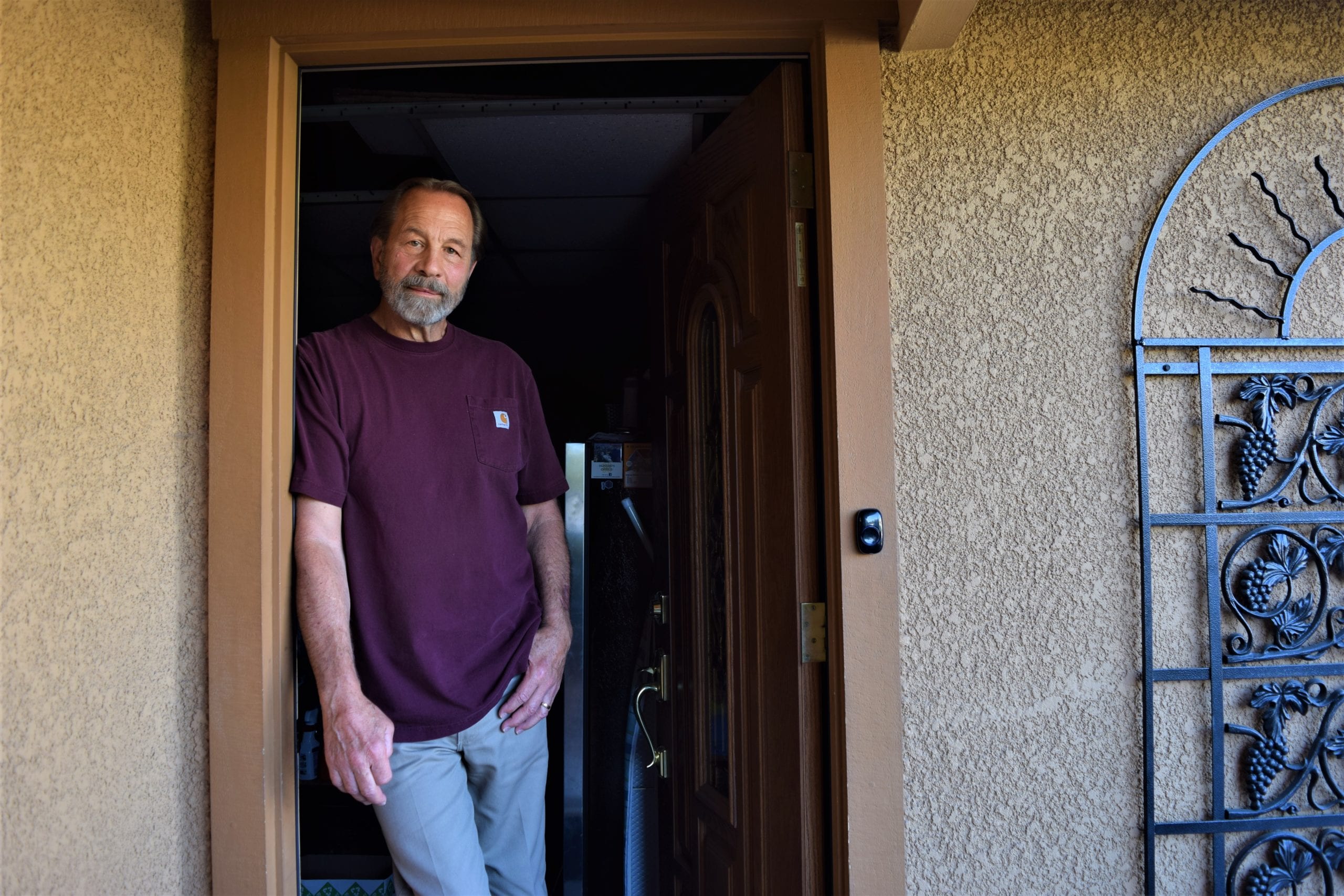

Steve Stender, who lives alone in a house near William Overfelt High School, said he previously lived with three of his high-school-age grandkids. At one point, Stender had eight people living in his three-bedroom home.

“My oldest grandson has had COVID already; he was totally asymptomatic,” Stender said. “So now he thinks he’s Superman.”

Stender said he’s worried about kids who often don’t practice social distancing when spending time with their friends, many of whom live with several other people. He also expressed concern about his neighbors having parties with large numbers of guests.

“They like to have their get-togethers,” Stender said. “Down the street, when the Niners play, you’ve got 15, 20, 30 people out front barbecuing, having a good time… no masks or anything.”

Esperanza Diaz, who lives with three people in a three-bedroom house in East San Jose, said she’s worried about catching the virus and being admitted to a hospital, where visitors aren’t allowed.

“I don’t trust the hospital,” Diaz said.

Despite its high infection rates from the outset, East San Jose had to fight to have additional testing sites in the neighborhood. Two new sites opened in April.

District 5 Councilmember Magdalena Carrasco said though the city has increased testing and contact tracing, her community is inherently at greater risk of contracting the virus due to the high number of essential workers.

“We continue to see the highest cases of COVID-19 in District 5 because the underlying factors are not changing,” Carrasco said, adding that many families work in crowded households and work two or three jobs just to pay rent.

Camarena, the mechanic who lives with five others, said until there’s a cure or a vaccine for the virus, people in his community will remain on edge.

“When you go outside, you don’t know if you’re going to get it,” Camarena said. “You don’t even know what’s going to happen if you get it. That’s the scary thing.”

Contact Sonya Herrera at [email protected] or follow @SMHsoftware on Twitter.

Mauricio La Plante contributed to this story.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.