A plan to densify housing in San Jose is sowing division and animosity in the South Bay.

Supporters hail it as a fix for the South Bay’s crippling housing shortage. Opponents call it a threat to suburban, single-family neighborhoods.

The plan, called Opportunity Housing, would allow developers to build up to four homes on a single parcel in neighborhoods limited to single-family homes.

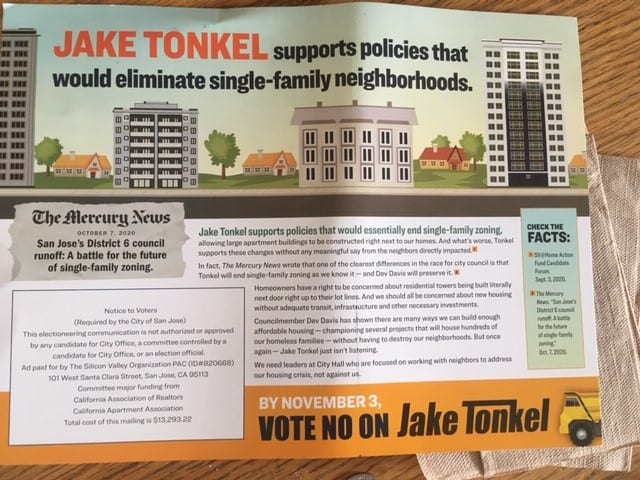

The issue took center stage this election cycle. Opponents attacked San Jose City Council candidate Jake Tonkel for supporting Opportunity Housing by sending mailers showing tall, gray towers built next to cheeky, colorful homes. The mailers drew the ire of housing advocates who penned a scathing letter calling it “blatantly deceptive” and demanded an apology.

So what does opportunity housing mean for homeowners and renters in San Jose?

The idea is to increase the city’s housing stock by allowing multi-units and more density in single-family neighborhoods — which comprise some 94% of the city.

Supporters say Opportunity Housing will increase the number of homes in the city and make housing more affordable, but the city — and state— has strict zoning laws prohibiting multi-family dwellings from being built on property designated for single-family homes.

In San Jose only 6% of residential property is zoned for multi-family homes.

“Opportunity Housing is something I really think our city needs to create socioeconomically diverse neighborhoods,” Tonkel said in a campaign video. “Our community is safer and healthier when we have neighborhoods everyone can afford to live in.”

Other cities with Opportunity Housing include Portland and Minneapolis. There have been only a few multi-family housing developments in these cities since they adopted the plan.

Question of character

The debate over densifying San Jose has pitted city leaders against one another, especially those who are fighting to maintain the “character” of their suburban neighborhoods.

San Jose Planning Commissioner Pierluigi Oliverio said the city owes it to its residents to maintain the integrity of the neighborhoods people moved into originally.

“All those individuals that either own or rent are there for a reason,” Oliverio said. “That’s the neighborhood they want. That’s the neighborhood they bought into.”

But Justin Lardinois, Oliverio’s colleague on the commission, denounced him for fear-mongering and leaning on “segregationist dog whistles.”

Lardinois said the insinuation that Opportunity Housing will “hurt home values,” create “chaos and conflict” and “damage neighborhoods” is dangerously similar to language used by mortgage lenders and the government in the postwar era to justify racial segregation and redlining.

“Let’s remember that all Opportunity Housing does is allow fourplexes,” Lardinois wrote. “Actually acquiring a property and converting it into a fourplex is a significant investment, so it will only happen in areas where it’s economically viable. What we’ll likely see is fourplexes lightly peppered throughout the city.”

Lydia Lo, a housing researcher at the Urban Institute, said Opportunity Housing wouldn’t shake up neighborhoods as much as people might think.

“When people think about densifying neighborhoods, they think about not being able to find parking and finding trash strewn everywhere, but with missing middle housing, you’re really just getting more homeowners who are really similar to you and your neighbors,” Lo said.

She said Opportunity Housing provides for “gentle densification,” where multiple units take up the same amount of space that a single-family home would occupy, making it a good option for a city facing a housing shortage.

Fear of developers

Olivero worries Opportunity Housing could lead to developers exploiting the plan for profit.

But Lo said San Jose’s bigger worry should be about potential inequities within neighborhoods.

“The benefits accrue to whoever is holding the land at the moment,” Lo said “So there are equity questions about who owns the land now and, thus, who would benefit from being able to build or sell these kinds of homes?”

Olivero said the city already is trying to level the playing field by creating more affordable housing, tiny homes, accessory dwelling units and other options. He maintains the city doesn’t need to break up single-family neighborhoods to continue doing so.

“It’s not like San Jose is not approving housing, because we’ve historically approved the most housing for the region,” Olivero said.

Despite efforts, the city still faces a shortage of affordable housing.

A San Jose renter would need to make $108,920 a year to afford a typical market-rate two bedroom apartment. A prospective home buyer would need to make $224,395 a year.

Rolando Bonilla, vice chair of the San Jose Planning Commission, said citywide Opportunity Housing could “help end inequities that we have had in San Jose for generations.”

But Bonilla is concerned about prioritizing Opportunity Housing only in urban villages or near transit hubs.

While the city will study implementing Opportunity Housing citywide, Bonilla said limiting housing options to transit-heavy areas would disproportionately affect San Jose’s downtown and East Side neighborhoods, which already have the most density.

“As a district, we carry more than our fair share of affordable housing, more than our fair share of policies that have not worked to our benefit,” Bonilla said. “We no longer want to be the city’s testing ground for policies because very often those policies never come with the adequate financial resources to actually make them work.”

Variety of housing

Some single-family neighborhoods already have duplexes and triplexes. According to the city, many of these were built before World War II when zoning laws were less restrictive.

Lo said even if San Jose approves a plan to implement Opportunity Housing, it won’t be accessible to working-class families for a while. The city needs to loosen restrictions to allow for variety in the housing market and find ways to subsidize the creation of multi-family units, she said.

The city’s general plan task force voted in August to recommend the City Council study enacting Opportunity Housing citywide, while prioritizing urban villages.

If the task force’s recommendations are approved, it will take the city about two years to draft an ordinance rezoning single-family neighborhoods. Plans for moving forward could come before the council as soon as next spring.

Contact Carly Wipf at [email protected] or follow @CarlyChristineW on Twitter

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.