As San Jose prepares to consider new framework for where to build affordable housing, questions remain about how to increase opportunities for low-income residents and people of color.

“Certain residents aren’t afforded the opportunity to live in higher-resource areas,” said Huascar Castro, associate director of housing and transportation policy at Working Partnerships USA. “The intent of the policy is to create opportunities where residents of all income levels are able to be in various parts of the city.”

San Jose held a series of meetings over the last year which resulted in a draft report detailing three tiers to prioritize for affordable housing. The areas are highlighted in an interactive map co-created by UC Berkeley’s Othering & Belonging Institute.

According to the report, the first tier includes “resource-rich” areas—wealthier neighborhoods “associated with upward mobility, educational attainment, physical and mental health, and other positive outcomes, particularly for children.”

This first tier includes areas such as Silver Creek, West San Jose and North San Jose near the proposed Berryessa BART Urban Village. Only 9% of the city’s affordable housing units are located in these affluent areas, according to the city’s report.

The second tier prioritizes areas at high risk of displacement with low levels of poverty and crime. These areas include Alum Rock, Luna Park, Seven Trees and Communications Hill.

The final tier targets areas that are also at high risk of displacement, but that rank higher in poverty or crime. These areas include downtown San Jose, Monterey Road between Alma and Curtner Avenue and the Meadowfair neighborhood near Eastridge Mall.

A lot of projects get concentrated in tier 3 neighborhoods such as downtown and Spartan Keyes, according to Sandy Perry, president of the Affordable Housing Network of Santa Clara County.

“I live in Spartan Keyes neighborhood, and a lot of people in our neighborhood feel like we’re being over-impacted by too much affordable housing,” Perry told San José Spotlight. “There gets to be an overconcentration of affordable housing that’s being built in areas that are the poorest areas.”

If approved by the City Council in August, the San Jose will concentrate funding affordable housing projects in the first two tiers. Perry said focusing affordable housing projects in poor areas increases segregation, but restricting funding too narrowly can jeopardize some much-needed housing projects.

“The only place where affordable housing can be built is where it’s legal to have multi-family housing, and that’s only on 7% of the city’s land,” Perry said. “I’m going to support affordable housing wherever it’s built, because it’s good and people need it.”

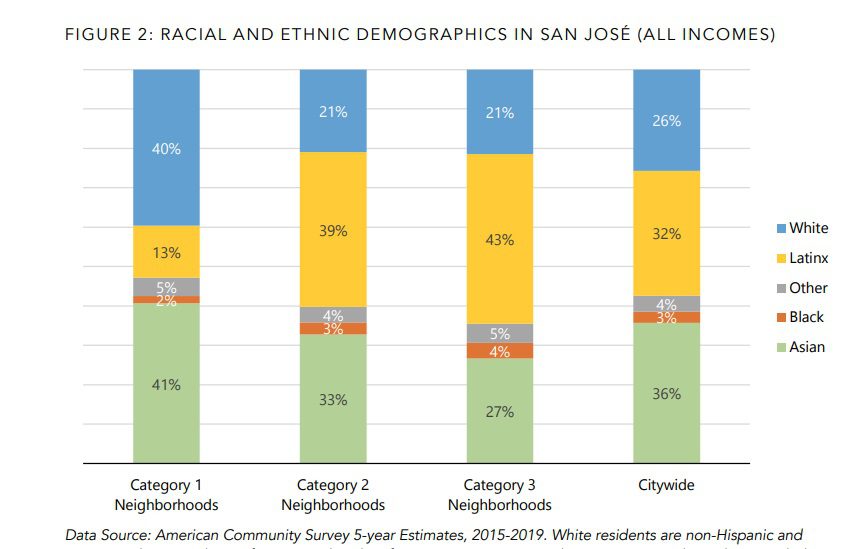

There are differences in the racial makeup of each tier, according to the city’s report. White and Asian residents make up 81% of the population in the first, most affluent tier.

Even when controlling for income, racial disparities remain in Black and Latino residents’ access to affluent areas. Low-income white residents live in first-tier neighborhoods at four times the rate of Black and Latino residents, according to the report.

In a memo to the City Council, San Jose Housing Director Jacky Morales-Ferrand recommends prioritizing 80% of affordable housing funding for the first two tiers of neighborhoods during the first three years of the proposed framework.

After three years pass, more funding should be allocated to first-tier neighborhoods, according to Morales-Ferrand.

Prioritizing funding for more affluent neighborhoods could jeopardize projects slated for lower-income areas that need more affordable housing, said Jaime Alvarado, co-chair of Alum Rock Urban Village Advocates.

“If you make that the rule going forward, there’s a lot of good projects that are happening that would be a benefit to the community—such as on the east side—and all of a sudden their funding is going to dry up,” Alvarado said.

Alvarado said it’s best to build affordable housing where people actually want it—such as low-income areas with high rates of overcrowding—and that some parts of the city oppose affordable housing more than others.

“They’re fine with it somewhere else, but not in their backyard,” Alvarado said. “They just assume it’s going to be a disaster each and every time, and that’s simply not true.”

Residents often worry about the impacts of new housing. However, affordable housing projects do not negatively affect property values in the areas in which they’re built, Morales-Ferrand wrote in her memo.

“A 10-year research study including 122 new low-income housing developments in the City of San José showed that the value of homes within 2,000 feet of new housing increased at the same rate as homes further away,” Morales-Ferrand wrote in the memo.

At the end of the day, Castro said more work remains to solve the problem of high housing costs in the region.

“This isn’t the end-all be-all,” Castro said. “There’s a lot of work that will follow.”

Contact Sonya Herrera at [email protected] or follow @SMHsoftware on Twitter.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.