Sand Hill Property Co. is planning a new 91-townhome development in Saratoga, but the project comes with a twist: the prominent developer is using a controversial state law to streamline city approvals.

Since Senate Bill 35 took effect in 2018, the law, which speeds up the development of certain housing projects, has been used only a handful of times in the Bay Area, generally for high-profile projects that have stalled in the past, or that developers fear may stall.

It’s the second time the law has been used by the Palo Alto-based Sand Hill properties, including the controversial Vallco Shopping Mall redevelopment in Cupertino.

Those concerns played a role in Saratoga, said Steve Lynch, Sand Hill’s director of planning and entitlement.

“Saratoga has a long history of cautiously approving residential projects that take years to ultimately come in front of council and they’re not always successful,” he said. “But in this case, the state offered us another avenue.”

On Thursday, Sand Hill Property Co. officials submitted plans to the city, announcing its intent to use the law to build the two- to four-bedroom townhomes alongside about 5,000 square feet of commercial space in place of the existing Quito Village retail center. The retail center today spans about 80,000 square feet in size, but it is 25 percent occupied, according to Sand Hill.

Even so, Saratoga Mayor Howard Miller said Thursday night he is “very disappointed that one of Saratoga’s few commercial areas could become predominantly residential and no longer serve the commercial needs of the neighborhood.”

If the project is approved through SB 35, each townhome would stand two stories tall, spanning 1,700 to 2,400 square feet and have a two-car garage. The site would include new green space, a community garden and a rose garden, a children’s play area and barbecues where today is primarily parking spaces.

Of the 91 for-sale homes, 10 percent — or nine townhomes — would be set aside as affordable homes, though the prices haven’t yet been set, Lynch said.

The proposal comes about a decade after Sand Hill purchased the stout shopping center at the corner of Paseo Presada and Cox Avenue. The center’s primary tenant, Gene’s Fine Foods, closed in late 2017 and Sand Hill has struggled to attract a new anchor retailer since.

“We bought this as a long-term hold, so this was an investment property; it was not bought as a redevelopment opportunity,” Lynch said. “Unfortunately, as the grocery industry and the retail industry just continued to crater, it’s turned into a redevelopment opportunity.”

Using SB 35 to push the project forward is a logical move, said Bob Staedler, president with land use consultancy Silicon Valley Synergy.

“It absolutely makes sense because they want certainty and a process they can count on,” he said. “Is there going to be the political will to not have shenanigans go on, is the question.”

Sand Hill first used SB 35 last year to overhaul Vallco Shopping Mall into a major mixed-use hub with millions of square feet of office, retail and community space alongside thousands of residential units.

Vallco’s redevelopment, which had been in limbo for years as city leaders and residents worked to figure out what they wanted on the 50-acre site, got the green light for development last summer because of the state law. But the developer is now facing legal challenges over that approval by a group of residents aiming to poke holes in the proposal and the law to halt the project, which they say is too dense and includes too much office space.

State Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco), who authored SB 35, told San Jose Spotlight in an interview earlier this year that the Vallco controversy had taught state leaders lessons in how to tighten parts of the law.

“Cupertino has done us the public service of exposing any ambiguity or loophole in the bill,” Wiener said. “So, we’ve actually passed several follow-up, clean-up laws to make clarifications and close loopholes.”

Though SB 35 can speed up approvals for certain development projects, the law also comes with a list of requirements and restrictions to qualify. And there is some uncertainty until all of the litigation around the projects that have already been proposed using the bill is resolved, Staedler said.

“Everyone is waiting for one (project) to get through the process and get through litigation and come out the other side,” he said. “It’s a canary in a coal mine situation.”

Among the requirements that SB 35 projects must meet: two-thirds of the space in the project must be for multifamily residential use, the development is required to be built by workers making prevailing wages — which is typical in union contracts — and it needs affordable housing, though the amount varies, based on whether each city is meeting its state-mandated goals to build new affordable housing, known as the Regional Housing Needs Assessment.

In Cupertino, Sand Hill is required by SB 35 to set aside half of the apartments at Vallco for residents earning less than the area median income. But in Saratoga, the state’s affordable housing requirement is lower, at only 10 percent of the units, because the town has not produced enough homes across the various categories in recent years.

Sand Hill’s proposal opts to make those nine affordable units available to people who are considered very low-income earners, one step further on the affordability scale than required by law. For Sand Hill, the difference between selling the homes at very low-income or just low-income prices was “negligible,” in the grand scheme of the project, Lynch said.

“Because we only have nine units, we wanted to bring something a little more significant than low-income (homes),” he said.

As of the end of 2018 — the most recent data available — Saratoga had produced no new very low-income-eligible homes, a category for people who make less than 50 percent of the area median income, state data shows.

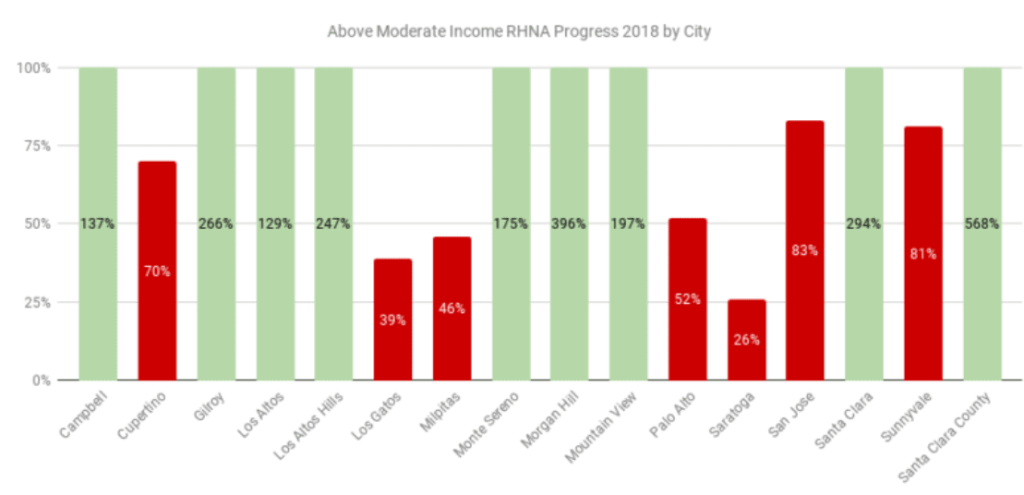

The city had also built 26 percent of its required units for people who made an “above moderate income,” which includes households making more than 120 percent of the area median income — a category that most cities in Santa Clara County have met or surpassed.

“We’re bringing new housing to a community that has shown itself to produce almost no housing over the last four years,” Lynch said. “We’re excited to help them meet their RHNA numbers on a shopping center site that … is a dead vacant site.”

Contact Janice Bitters at [email protected] or follow @JaniceBitters on Twitter.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect that Saratoga has not produced enough “above moderate housing” in recent years, in matching with the graph in the story. A previous version of this story only said “moderate housing,” which is a separate category. We regret the error.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.