Silicon Valley has seen massive growth since the 2008 Great Recession, but one local market expert estimates the market is “frothy,” signaling that the region may have finally hit a peak and could begin to slow in the near future.

“Most of the people from San Francisco, Silicon Valley, think that we’re probably in the top of the cycle,” said Alexander Quinn, JLL’s director of research for Northern California, during the annual Silicon Valley Economic Development Alliance conference in Santa Cruz this month. “(In) Oakland, East Bay, Sacramento, there is still some room for growth there.”

As the end of 2019 approaches, researchers and analysts are trying their best to estimate what will come in the next year or two. Last year, many economists said that while they didn’t see a recession on the horizon, history shows that what goes up must come down and the Bay Area is in unprecedented territory with about nine years of consecutive economic growth.

The question is: when will that growth slow or invert, and how hard will the economy fall in a region that Quinn said is currently “hitting above its weight” in terms of venture capital investment?

While the San Francisco-based research director for JLL says he doesn’t have a crystal ball to know the future, he warns the Bay Area economy isn’t going to grow forever. That’s a familiar echo of what Santa Clara County Assessor Larry Stone has also been warning for years as he urges leaders not to let Silicon Valley go the way of Detroit due to housing and infrastructure issues.

Indeed, like Stone, Quinn sees several headwinds for Silicon Valley, including the housing and labor shortage, the cost to rent or own space in the region, and construction costs. And though companies are still looking for millions of square feet of space to lease in the region, Quinn said companies are also beginning to look elsewhere for growth.

“What you’re going to hear in the next few months — we might hear it already — is major lease agreements in New York, Chicago, with Google making plays outside of California,” he said. “It’s not because it’s incredibly expensive (in Silicon Valley), which is part of it, but it’s because room to grow in terms of labor does not exist in the Bay Area.”

Between 2009 and 2017, Silicon Valley outpaced every other major region when it comes to gross domestic product growth, according to the brokerage’s data. But Quinn likens the Bay Area’s economic cycles to a series of “gold rushes.”

“We go through (gold rushes), we fall on our face, we lose all our money, come back again about 10 years later, and we do it over and over again,” he said. “We’re at kind of a gold rush frothy period right now.”

So what does a “gold rush frothy period” look like, and what are the issues that could tamp down on that froth?

The gold rush

Since the recession, Silicon Valley has shifted from about 11.3 percent unemployment to 2.3 percent as of October. The region has added about 800,000 employees over the last decade, Quinn said. The median home price today is more than $1 million in Santa Clara County and the Bay Area is consistently ranked one of the most expensive places to live in the country.

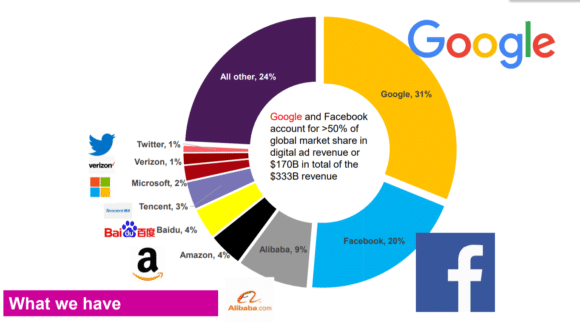

About 47 percent of all venture capital spending in the U.S. is coming to the Bay Area, according to JLL data. Meanwhile, Bay Area startups-turned-titans, Google and Facebook, now account for more than 50 percent of market share for digital ad revenue globally.

Companies have also put out feelers for nearly 9 million square feet of commercial space in Silicon Valley. Life sciences and technology continue to be the sectors growing the most, while cities try — with varying degrees of success — to diversify their base of companies.

“You want to have a variety of employment opportunities within your city,” Quinn said.

The headwinds

But the Bay Area is also facing some headwinds that researchers say are already limiting the region’s growth. A 2015 study released by the National Bureau of Economic Research estimated that if not for the housing shortages in some of the most high-paying cities in the country, GDP could rise by 9.5 percent.

“It’s a market failure that exacerbates social inequities, meaning that low-income households can’t live in the neighborhoods that produced the most exceptional economic mobility,” said Michael Kingsella, executive director for Up for Growth, an affordable housing nonprofit thinktank. Kingsella also spoke at the SVEDA conference this month.

Employers are struggling to get the employees they need, but the cost to lease commercial space also plays a part, Quinn said.

“This is what economic development agencies outside of the Bay Area are telling employers in the Bay Area — how much money you can save if you leave,” he said. “For my compadres in Texas, JLL has a marketing deck specifically to target Bay Area employers.”

Contact Janice Bitters at [email protected] or follow @JaniceBitters on Twitter.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.