The high costs of building in San Jose, among the highest in the state, imperil the supply of a crucial source of financing for affordable housing: state tax credits.

“Each year, these programs change their funding requirements,” Michael Lane, state policy director at urban planning think tank SPUR, told San José Spotlight. “It takes multiple years to put one of these projects together, and if they’re changing the rules, it makes it very challenging.”

According to Lane, the state is awarding fewer tax credits to Bay Area projects due to the high cost of building compared to other areas in the state.

“They’ll say, ‘We can build for $400,000 a unit in Stockton, versus $600,000 per unit in San Jose, so we’ll build in Stockton,’” Lane said. “But then the workers are driving back to Stockton from San Jose.”

When Park Avenue Senior Apartments were built last year—including 99 affordable units and one manager unit—there was much to celebrate.

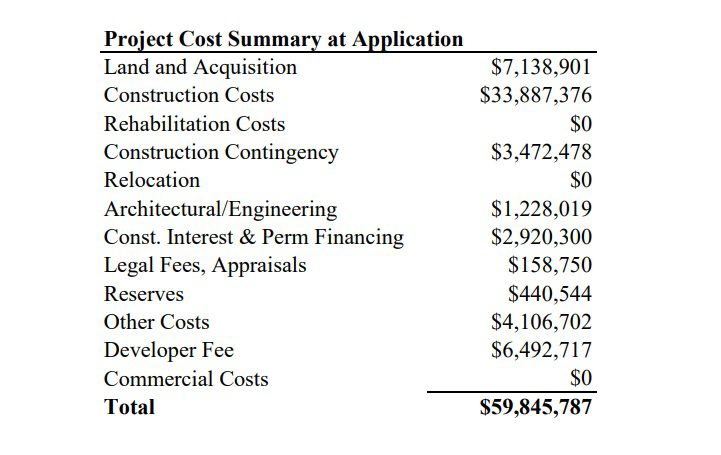

But the development cost $59,845,787 to build, which amounts to $604,502 for each affordable unit.

Affordable housing projects like Park Avenue are financed through a “capital stack” using four to seven sources of funding, according to Lane. Federal and state tax credits are awarded to developers in exchange for building affordable housing. Developers then sell these credits to investors who use them to lower the income tax burden.

The California State Treasurer’s Office recommended $6.3 million in tax credits to fund Park Avenue Senior Apartments, more than 10% of the project’s total cost.

Affordable housing projects also use funds from the county and city. Santa Clara County’s Measure A, passed in 2016, is used to buy or build upon land for affordable housing. San Jose’s Measure E, passed in 2020, uses an increased real estate transfer tax to raise an estimated $50 million a year for affordable housing.

Developers also seek out private loans from banks and other investors, Lane said, which help cover construction, often the most fluid and pricey of the costs due to the fluctuating price of materials such as lumber and concrete.

Jeff Scott, spokesperson for the San Jose housing department, said the city has trouble acquiring enough tax credits to fund affordable housing needs. Santa Clara County aims to build 4,800 affordable units by 2026, while San Jose plans to build 10,000 affordable homes by 2022.

The majority of building costs come from construction, which totaled about $33 million for Park Avenue Senior Apartments—or 56% of the cost. Construction costs are high for all types of housing in the Bay Area, with 71% of those costs coming from materials, equipment and wages.

Land acquisition is also costly, amounting to about $7 million for the Park Avenue Senior Apartments. Land is sold at $10 million an acre around Diridon Station near the apartment complex.

Scott said that construction and land acquisition are among the highest costs of building affordable housing in the city. But new technologies and frameworks could speed up building and bring down the price of construction.

“The supply of modular units and the industry getting used to financing modular construction are both works in progress,” he said. “Mass timber is also a promising technology that the building code now supports.”

Scott said about 45% of San Jose’s residents are considered lower income and qualify for tax credit housing, but only about a quarter of the city’s housing stock is rent-restricted affordable apartments.

“We need a lot more supply than we have,” he said.

All in all, preserving rather than building new affordable housing is a more cost-effective method for increasing supply. The cost of acquiring and rehabilitating housing to be preserved as affordable ranges from $275,000 to $480,000 per unit, according to San Jose’s Affordable Housing Implementation Plan for the Diridon area.

“Preserving affordable housing can be as little as only half of the cost of new units,” said Sandy Perry, president of the Affordable Housing Network of Santa Clara County. “It’s a very good investment from that point of view.”

Perry said rehabilitating existing housing units through community land trusts, such as the South Bay Community Land Trust, can also keep them permanently affordable. Land trusts can target residents whose incomes fall below the low-income limits outlined by the county.

“The median income of Santa Clara County rises much faster than people’s fixed income and people’s wages,” Perry said. “Even the affordable housing becomes unaffordable over a period of time.”

The median household income in Santa Clara County is $126,606, according to Data USA. An individual resident would have to earn $58,000 or less to qualify for a low-income apartment, according to the Santa Clara County Housing Authority.

The South Bay Community Land Trust is working on acquiring its first property this year. Perry said it’s a promising model, particularly considering the $5 million that San Jose allocated toward the preservation of affordable housing.

“They have the funding, we just have to convince them that we can make some use of it,” Perry said. “It’s an idea whose time has come.”

Contact Sonya Herrera at [email protected] or follow @SMHsoftware on Twitter.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.