It’s the go-to spot for some of Silicon Valley’s elite. Politicos, executives and the area’s top movers and shakers shell out $200-plus a month just to walk through the 17th-story doors of the exclusive Silicon Valley Capital Club.

But while many members drive up to the lavish business club atop the downtown San Jose KQED building in Teslas and Maseratis, employees say they’re underpaid because of a secretive compensation system and a club policy that prohibits tipping. Many employees say they’re scraping pennies together to make ends meet.

The reason behind the struggle? Capital Club pays its service workers less than minimum wage. The club boosts salaries with money from a “service charge” pool – one percent to each employee. But workers say they have no clue how much money is in the pool, and some claim they’re being shortchanged.

Workers also say they’re being cheated out of tips since the club discourages tipping and some customers mistakenly confuse the hefty service charge as the tip. It’s an issue that’s become a hot debate in the service industry and has plagued some of the fanciest restaurants in the area like Berkeley’s Chez Panisse.

“(My girlfriend) had to pawn some of her gold jewelry just to get groceries, to get gas and to pay rent,” said Gabe, a former Capital Club server, who asked to withhold his last name for fear of retribution. “I didn’t really think about it at that moment, but it actually is kind of sickening.”

Gabe’s story isn’t unique among his fellow Capital Club employees.

He said many of his ex-coworkers were forced to squeeze multiple tenants into a one bedroom or live without furniture in a tiny studio apartment.

Many current and former employees said they’ve voiced wage concerns to management with no luck. Instead, they claim, they’ve experienced retaliation for speaking out, such as losing desirable shifts.

According to a wage document obtained by San José Spotlight, the Capital Club paid Gabe a base pay of $7 per hour. San Jose’s minimum wage was $10.30 an hour when Gabe was hired in 2016 and climbed to $13.50 an hour when he quit in 2018. During that time, his pay remained unchanged.

The club pays most of its employees one percent of the weekly service charge pool to make up for sub-minimum wages. The money in the service charge pool comes from an automatic 20 percent charged to all food and beverage bills. But customers are discouraged from tipping because of the charge, workers say.

“As far as trying to find some transparency on the service charge on a week to week basis, it’s sort of in closed amounts,” says a current lounge employee who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation. “(Management is) not very upfront with giving it and there’s a lot of I don’t know and just wait and see.”

General Manager Bruce MacKenzie said he’s never been asked for that figure and said the club is happy to disclose employees’ hourly share.

The lounge employee, however, said the money is automatically tacked onto their paychecks. He blamed the secretive compensation system on Food and Beverage Director Justin Stuyt, who he claims brushed off requests for information. Stuyt did not respond to requests for comment.

Claims of money mismanagement and unfair wages

Employees’ skepticism over fair pay stems back to previous claims of money mismanagement.

According to former supervisor Joanna Amalato, food and beverage director Milagros Gomez was paid out of the one percent service charge pool while on maternity leave, cutting into the money due to the wait staff.

And Amalato experienced her own issues with pay and alleged retaliation.

In 2017, she filed a retaliation complaint and a claim for unpaid wages with the California Labor Commissioner’s Office. Her complaint stated that she was “mistreated, harassed, suppressed and scrutinized by Food and Beverage Director Justin Stuyt and Chef Ron Garrido.”

“I was throwing up and I was crying,” Amalato said. “I have values so it’s very hard for me to read or see certain things. I just felt like my general manager had all this power and there was no way for me to continue to take part in that.”

In her unpaid wages claim to the Labor Commissioner’s Office, Amalato requested $383 that the Capital Club owed her for unpaid meal break wages. Amalato was awarded the compensation.

According to California law, employees must be given a 30 minute meal break every five hours. If they don’t, employers must pay the employee an additional hour of pay for compensation. Amalato said she received neither.

The lounge employee also questioned his paycheck, saying he was promoted but never told how much he’d earn. Amalato said she alerted MacKenzie, the club’s general manager, who allegedly said, “just leave it, he probably doesn’t look at his paycheck.”

Gabe corroborated the story and the lounge employee said he was eventually paid back about $800.

With an apparent lack of clarity from management, Gabe said he often compared paychecks with coworkers to find out if he was getting his fair share of the service charge pool. He claims Stuyt verbally reprimanded him and a fellow employee for doing so.

Santa Clara University law professor Ruth Silver Taube said that type of backlash is illegal and employees have a legal right to discuss their salaries. State and federal labor laws prohibit employers from disciplining workers for discussing wages with colleagues.

Tipping prohibited

Another point of contention for Capital Club workers is an unfavorable tipping policy.

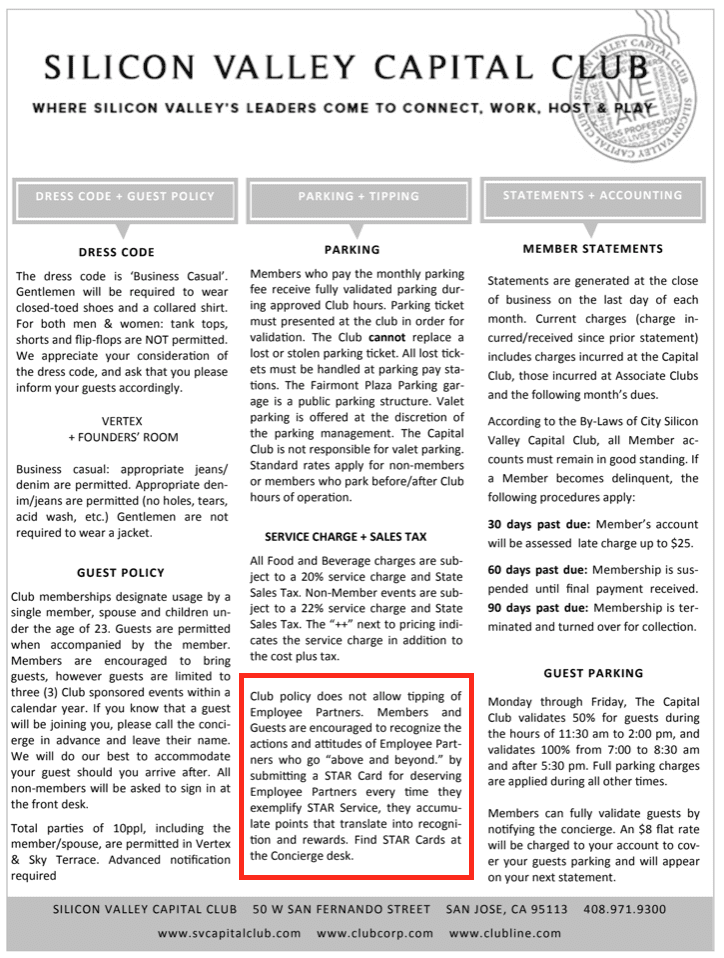

Membership literature from July 2018 indicates that the club bans tipping and instead asks patrons to fill out a form when they receive exceptional service.

Gabe claims that Stuyt threatened to fire employees who try to get tips.

MacKenzie said tipping is not prohibited. The longtime manager also claimed he had no recollection of the document that discourages members from tipping. Instead, he said the club discourages servers from soliciting tips.

Some club employees fear that the automatic service charge is being mistaken for a tip.

Silver Taube said it’s a valid concern.

“People I know who go to the club believe that the money is in lieu of a tip and that it is all going to the employees,” she said. “The employer does nothing to dispel this misconception, and the workers at the Capital Club lose out.”

Some municipalities have passed laws to eliminate the confusion. In Santa Monica, employers must split service charges among employees, while supervisors are prohibited from pocketing any of it, Silver Taube explains.

“We need such an ordinance in Santa Clara County,” she said.

Contact Grace Hase at [email protected] or follow @grace_hase on Twitter.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.