During the annual State of the Valley conference on Friday, top Silicon Valley leaders highlighted how the gap between rich and poor is widening in the region and how workers may find themselves stressed to death, even as the regional economy continues to grow.

The sold-out event, which featured a keynote address by iconic journalist Dan Rather, centered around the 2020 Silicon Valley Index by Joint Venture Silicon Valley and its Silicon Valley Institute for Regional Studies. The annual research and benchmarking report, released Wednesday ahead of the organization’s annual State of the Valley event, shows the cost of living is rising, tech jobs are growing faster than ever and income inequality in the region reaches new heights.

The conference featured speakers including Margaret O’Mara, a history professor at the University of Washington, who mapped out how Silicon Valley became the epicenter of tech — but warned that the region should not take its position for granted.

“In 1920, when Prune Week was the biggest thing happening in San Jose, the most innovative place in the world was Detroit,” she said Friday. “Detroit is still the center of mass innovation but Detroit is also now an example put up of ‘This is what happens when things go wrong with a city, with its economy, when you don’t invest in place and people.'”

Revered urban planner Peter Calthorpe advocated for the Bay Area and the entire United States to embrace the concept of more dense mixed-use “Grand Boulevards,” using El Camino Real as a prime example. If the 43-miles of El Camino were up-zoned for mixed-use development, the region could add upwards of 250,000 new homes along the thoroughfare that links cites across the Bay Area without cutting into existing single-family neighborhoods.

“In-fill is the answer and we have these ribbons that can become a network of urbanism that enhances all the communities around them,” he said.

Rather, a beloved CBS News anchor, delivered a keynote address that focused on the state of journalism today and the part tech companies play in the decline of newspapers across the country.

“I believe there still is a sunny optimism and idealism, a belief — a deep belief — in Silicon Valley that technology can improve the human condition,” he said. “What it will take in part to do that is no small amount of self reflection. There will be change from the outside in the form of new government oversight, shifting consumer demands, but a lot of it can come internally.”

He called on leaders to help find solutions for sustainable journalism — a business model that works — amid a rapidly shifting digital era, including the reliance on social media. He also addressed the so-called “liberal bias” of the media, saying that journalists often tell stories of the homeless, heartbroken and hopeless — and that can be misinterpreted as being liberal.

“If that makes you a liberal, then liberal I am,” he said to applause.

Rather spent a few minutes talking about California’s rapidly approaching primary election, saying candidate Mike Bloomberg — who is endorsed by Mayor Sam Liccardo — must win California to stay in the race. He predicted Bernie Sanders would make it to the end of the race.

The index on health and inequality

Like the event Friday, the report, called the Silicon Valley Index, touches on data points from virtually every part of the Bay Area, from development, tech, traffic and housing. New to the report this year is health data, which shows the rate of deaths caused by hypertension and hypertensive renal disease in the region has increased by 270 percent since 1999, the report found. Though hypertension is not always linked to stress, lack of sleep and stress can contribute to the disease, according to the Mayo Clinic.

The problem tends to be worse for those who have less money, said Rachel Massaro, vice president and director of research for the Silicon Valley Institute for Regional Studies.

“It’s a silent killer because not everybody knows they have hypertension, and they don’t necessarily see a doctor if they don’t think they can afford it, or they don’t have money to pay their co-pay,” she said. “Certainly those are some of the things that play into the death rate.”

Business and building reach record highs

Silicon Valley hit other records in 2019, including an 18-year high when it comes to newly completed commercial space, which spanned a combined 8.5 million square feet. Unemployment has also dipped to a 19-year low of 2.1 percent as the region is in its ninth consecutive year of economic growth.

That means employees are filling office space even as housing development fails to keep up with the rate of commercial developments. Since the 2008 recession began to lift, the Bay Area has added 821,000 jobs, but just 173,000 new homes, according to Joint Venture data — a 5:1 ratio.

The trend is driving costly housing in the region, and the issue “doesn’t seem to be budging,” said Russell Hancock, president and CEO of Joint Venture Silicon Valley.

In large part, the standstill is because many aren’t interested in adding significant housing to the region, he said. Residents often see large housing projects negatively and lobby city councilmembers to reject such developments when they’re proposed, he added.

“That’s all fine if that is the will of the community,” Hancock said. “But the community has not communicated that to the economy.”

Job growth is slowing, however. Silicon Valley companies added nearly 30,000 new positions — a growth rate of about 1.7 percent — between the second quarter of 2018 and 2019, outpacing the state and nation. The job growth rate was 2.2 percent in the 12 months before.

The relative jobs slowdown is not surprising considering the low unemployment, said Hancock.

“We should think about this as an economy at full employment,” he said. “We don’t have as many jobs to create and if we did, we wouldn’t have anybody to fill them because we are all employed.”

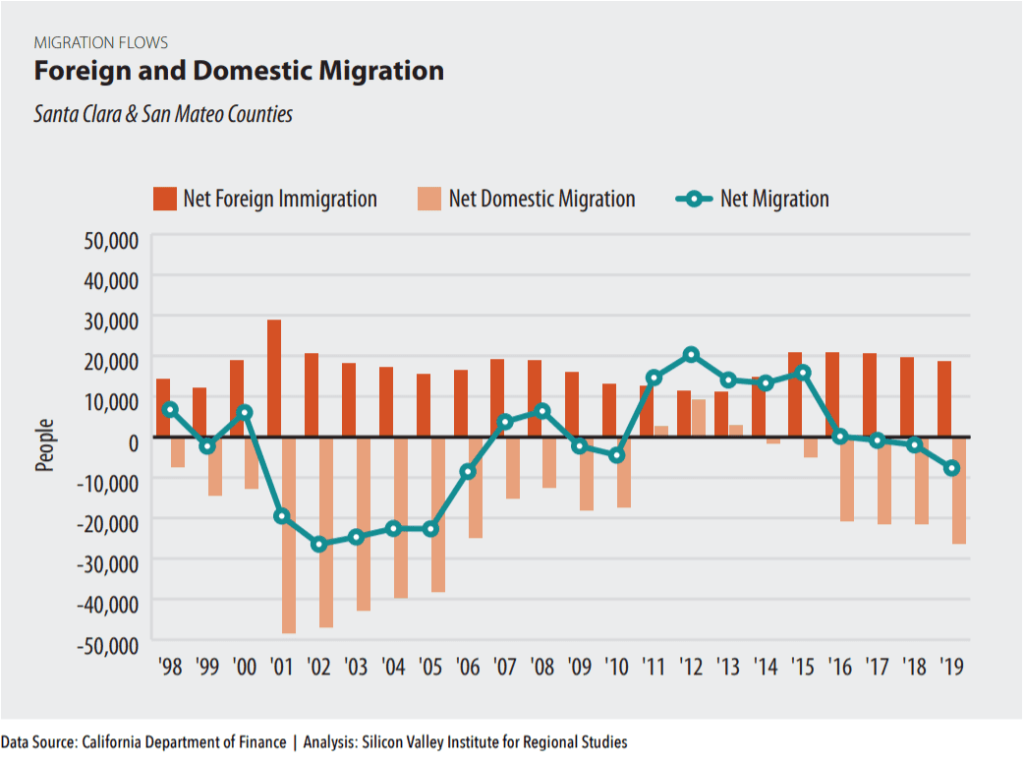

The result is that those coming into the region today tend to be highly educated workers from overseas. And while those international arrivals help to fill out the high-tech job market, the data shows that more people left the region than came in for the third year in a row. Those who are coming, tend be be landing high-paying jobs, often at or above $200,000 a year or more, the data shows.

Housing and traffic aren’t budging

Many of the reasons for the region’s net negative migration aren’t a mystery to Hancock, who focused in on housing and traffic — two major quality of life factors.

Median home prices in Silicon Valley remain above $1 million, pushing many local workers to areas farther away from their jobs and contributing to the Bay Area’s notoriously heavy and unpredictable traffic. Transit ridership hasn’t increased even as commutes lengthen, with about 73 percent of people driving to work alone. Meanwhile, tech companies continue to provide transit to their own workers with a fleet of buses that rivals every other transportation system in the area.

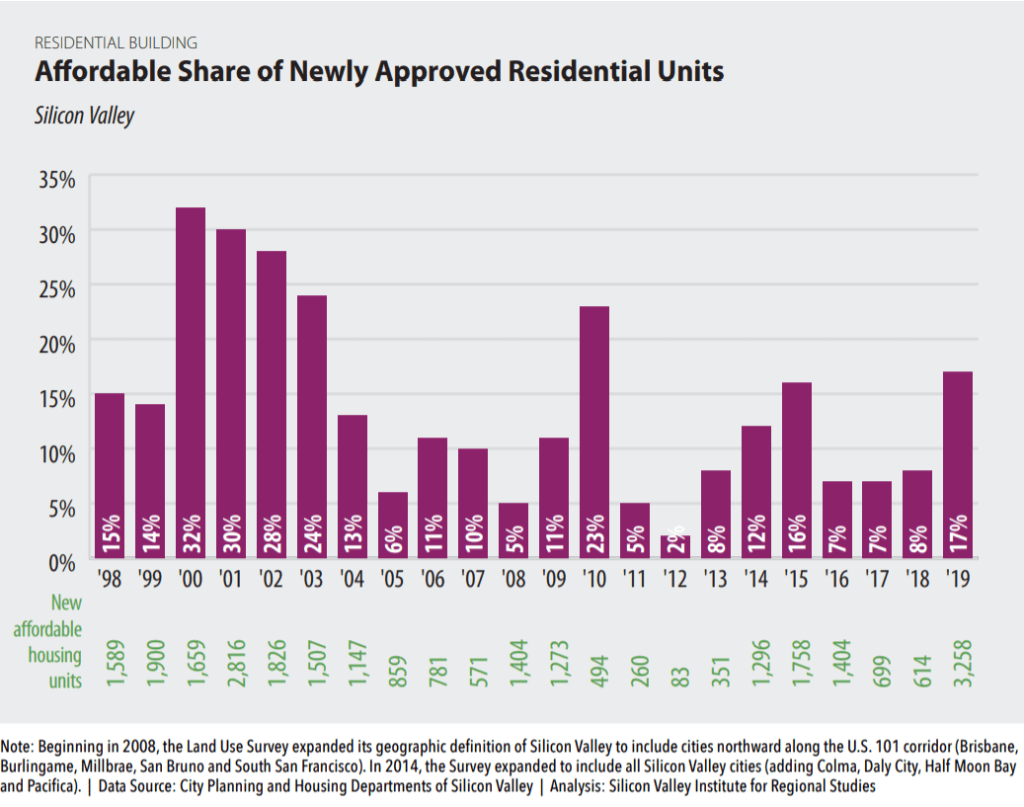

One bright spot, Massaro said, is that more affordable homes and denser developers were approved in the region over the past year than in the preceding 20 years.

“The data is showing over the next coming few years we are likely going to see a lot more dense housing and affordable housing,” she said.

Meanwhile, 83 percent of the homes permitted to begin construction over the last four years are considered luxury and out of reach financially for many renters.

“It’s our Achilles heel and it’s killing us,” Hancock said. “The reasons are clear: We are not building enough.”

Venture capital is ‘clumping’

Venture capitalists are also gravitating toward the rich in the Bay Area, dumping $42 billion into local businesses last year, but about half –92 of those deals — were megadeals with companies that are already highly valued, the data shows.

That’s a shift away from past venture capital culture, which attempted to get in on the ground level of a promising company, often run out of a Bay Area garage, Hancock said.

The trend shows that like with Silicon Valley residents, those with money and clout increasingly getting more while those who don’t have found resources more scarce.

“Money is clumping,” Hancock said. “The philosophers among us are wondering if we are starting to change the nature of innovation in Silicon Valley and the way it is taking place.”

Contact Janice Bitters at [email protected] or follow @JaniceBitters on Twitter.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.