It may be hard to imagine now, but there was a time when a majority of San Jose and Santa Clara County voters rejected an opportunity to ban discrimination against the LGBTQ people among them.

“’Gay people are so disgusting they deserve no rights, and we don’t even want them in town.’ That was the prevalent attitude of people living in the South Bay,” said former Santa Clara County Supervisor Ken Yeager, who was the first openly gay city and county lawmaker.

The fight for those rights and a seat at the table, launched Yeager’s career and led to the founding of a life-changing center, the Billy DeFrank LGBTQ+ Community Center, which celebrated its 40th anniversary this month.

In 1979, the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors and San Jose City Council decided to put measures before voters that would ban discrimination based upon sexual orientation, extending housing and employment protections to gays and lesbians. The measures were known as A and B.

The campaign was brutal. The religious right had denounced the ordinances, taking positions that portrayed gays and lesbians as sexual predators. At the polls in 1980, voters rejected both measures, essentially supporting discrimination against the LGBTQ community.

Yeager, who founded Queer Silicon Valley, said the lack of local support of Measures A and B and gay rights was a catalyst for Silicon Valley’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer community.

“Everything that happened in the last 40 years goes back to Measures A and B,” he said.

The year after voters rejected the twin measures, the DeFrank Center opened its doors. It would be another 12 years before workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation was made illegal. But, in March 1981, a safe place for the LGBTQ+ community became real—it grew into a jumping point for a political movement, parade and gathering spot.

“They were so disheartened by the Measures A and B campaign,” Yeager said. “They wanted to have a sense of community to show they were responsible, productive members of society — not what was being portrayed by the religious right.”

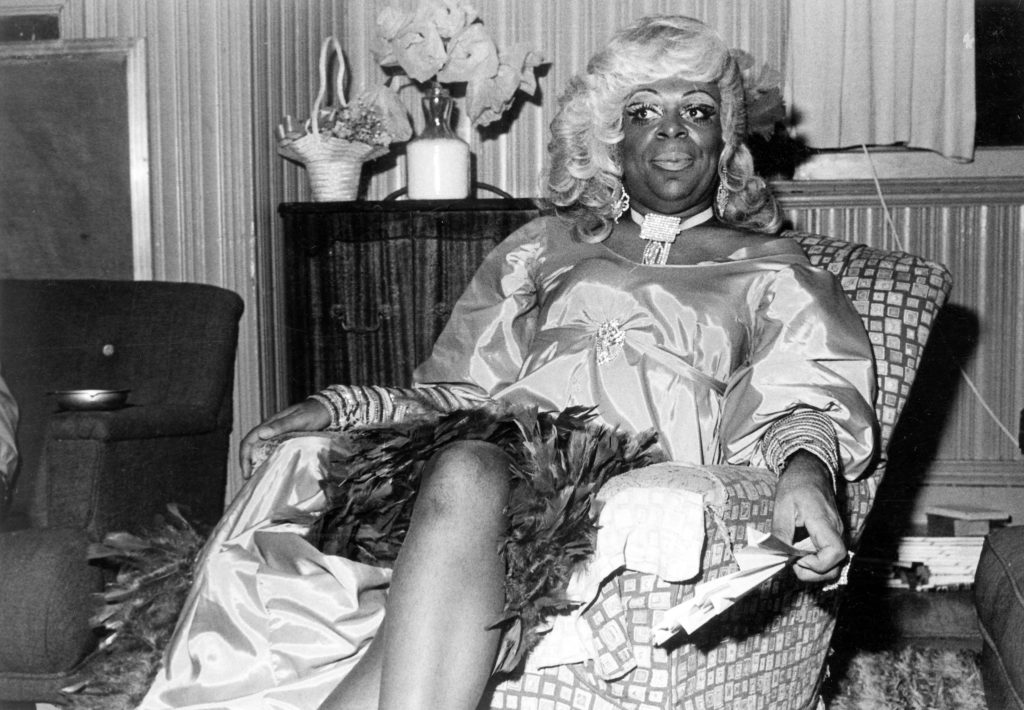

The DeFrank Center, which was named after activist William Price, whose drag queen name was Billy DeFrank, now serves more than a thousand people monthly in its current location on The Alameda.

“We’re trying to find ways to make it a home for everybody,” said Gabrielle Antolovich, board president of the DeFrank Center.

Founding the space alone didn’t solve the problems. The people inside had to organize to change the community.

Battles ahead

In 1984, former Assemblymember Alister McAlister wrote an op-ed in the Mercury News arguing that men who love other men should have no legal, social, or political standing in society. McAlister was advocating for Gov. George Deukmejian to veto yet another opportunity to ban discrimination based on sexual orientation.

“McAlister said gays are so unwanted in our society and are so sinful that they don’t deserve any recognition as a class of people you can’t discriminate against,” Yeager said.

Yeager said he realized if he didn’t fight for his own rights, nobody else would. A week later, Yeager came out publicly with his own op-ed denouncing McAlister and urging for acceptance of gays and lesbians.

He joined forces with a longtime political activist, Wiggsy Sivertsen, to found the Bay Area Municipal Elections Committee (BAYMEC), a political action committee that endorses candidates, held elected officials accountable and promoted LGBTQ rights.

“It was our only way to fight back and at least have a voice,” Yeager said. “We had been totally stomped upon.”

Their efforts laid the groundwork for what was to come.

Silicon Valley Pride

Every summer, a parade of rainbow glitter streams down Market Street in downtown San Jose. Mascots of local sports teams pass tchotchkes to kids. Politicians of nearly every background march, too. It seems simple. But it’s something activists fought for.

The San Jose City Council planned to issue a proclamation for Gay Pride Week for the first time in 1978, two years after the city’s pride parade sprang into being. Backlash killed the idea. Members of the Christian right faced off against a rally held by the gay community.

In June 1993, officials tried again. County Supervisor Ron Gonzales introduced a resolution declaring Lesbian and Gay Pride Week in Santa Clara County. San Jose didn’t come on board until 2001 when then-councilmember Yeager proposed it.

Now, Silicon Valley Pride and the DeFrank Center work hand in hand on events and endeavors.

“Without the Billy DeFrank Center and the strides it’s made in this community, Silicon Valley Pride would not be where it is today,” said Nicole Altamirano, chief executive officer of Silicon Valley Pride. “We’re constantly partnering with one another and holding each other up.”

And the celebration, like all things, remains a work in progress.

Saldy Suriben, chief marketing officer of Silicon Valley Pride, said the group recently changed its logo to be more inclusive and represent Black, brown, indigenous, people of color (BIPOC), and transgender individuals.

“That’s something we need to focus on,” Altamirano said, “bringing those marginalized groups in our community together and reinforcing that we all belong to this community and that we make up this beautiful rainbow of color.” Streets of rainbows

By 2016, the tone had dramatically changed. Antolovich worked with Mayor Sam Liccardo to create a rainbow crosswalk on The Alameda. At its unveiling, more than 400 people showed up to celebrate including Yeager, Assemblymember Ash Kalra and then-Councilmember Johnny Khamis.

“In a city where we don’t have a lot of symbols showing LBGTQ history, it’s wonderful to have,” Yeager said. “It brings me a big smile, like the rainbow flag flying daily at the county building. Whether a flag or a crosswalk…it’s a sign of welcoming and acceptance of everybody. It says whoever you are, we accept you.”

Although things have come a long way from the time when voters rejected protections for LGBTQ rights, leaders say it’s not enough. It’s also easy to forget California voters rejected an opportunity to make same-sex marriage legal in 2008. Seven years later, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the freedom to marry, allowing same-sex marriage in all 50 states.

Support tomorrow

Today, the LGBTQ+ community is fighting for the Equality Act, a bill that prohibits discrimination based on sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity in public accommodations and facilities, education, federal funding, employment, housing, credit, and the court system. In February, it passed the U.S. House of Representatives and is now in the Senate.

That’s not all that is needed, Yaeger said. LGBTQ+ youth still face discrimination and rejection. Schools, counselors and parents need to ensure these kids have support.

“I can’t tell you how awful it is for LGBTQ+ teenagers to be kicked out of their house when they tell their parents or their parents find out that they’re gay,” Yeager said, “and there they are on the street with unbelievable hardships.”

Antolovich agreed and said it is why the DeFrank Center remains important 40 years on.

“We are the only minority who gets kicked out of the family for being who we are,” Antolovich said. “Other minorities stick together against the world. We’re the only ones who get kicked out. So, having a center where you can be who you are and develop who you are…that is the service…the space itself where it’s safe to be who you are.”

To learn more about the history of the LGBTQ movement in Santa Clara County, please visit Queer Silicon Valley.

Contact Lorraine Gabbert at [email protected].

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.