When Gavin Newsom became California’s governor, he announced a bold goal of solving the state’s 3.5 million-home shortage by 2025, but there’s one major problem: cities across the state are only planning for about 2.8 million new housing units.

What’s more, many of the areas where those 2.8 million new homes are allowed to rise, based on current city planning documents, are rural, where demand for housing is less and jobs remain a long car ride away, according to a 2019 report from the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies.

But one nonprofit says closing that housing shortage gap — and more — as well as increasing the state’s GDP and reducing car travel is within reach for the state, if local policymakers rethink traditional zoning trends.

Specifically, Washington D.C.-based housing thinktank Up for Growth encourages building more mid-rise and higher density housing near transit, which may mean increasing the density in and around some single-family neighborhoods and places with the most jobs.

“We’re really shifting more from the low density … single-family format to more of a middle density,” said Michael Kingsella, executive director at Up for Growth. “So whether that’s mid-rise podium, four- or five-story mid-rise buildings in downtown or transit center locations to the missing middle typologies like ADU’s, duplexes, triplexes and cottage clusters.”

The pitch, delivered during the annual Silicon Valley Economic Development Alliance convention in Santa Cruz this month, comes as housing remains one of the top issues for California leaders grappling with how to address rising rents that are pushing people out of their homes and into the streets or to cities far from their jobs or support networks. While the problem is obvious, fixing the issue is not so clear-cut.

As the UCLA report points out, even if 3.5 million homes were currently allowed to rise across the state, only a fraction of the number of city-planned homes ever get built.

Sometimes those homes are permitted to rise in areas where people aren’t eager to live, so developers aren’t eager to build, for instance. Sometimes developments shrink in size due to land use policies like parking requirements or community opposition. To get 3.5 million homes rising in the state, cities must plan for many more than that — and they must be planned for areas where people want to live, the UCLA report states.

“The limited new housing construction in California in the face of increasingly high rents and prices presents a challenge: high demand communities do not plan for or permit housing and planned capacity in low-demand areas remains unbuilt,” the report says.

That’s Up for Growth’s entire pitch: plan for growth in targeted, high-demand areas, which would mean upzoning those areas, allowing more duplexes and triplexes to integrate with single-family homes, to push forward more high-density projects near transit than the state does today.

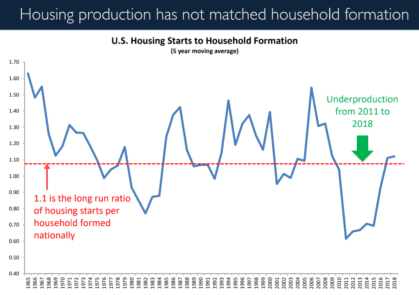

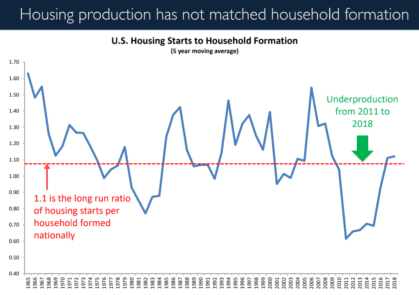

But it’s not quite that easy. Proposing such changes can be a tenuous position for politicians and community advocates who need buy-in from local homeowners. It would also be a significant change for California, which has been producing less housing per capita than ever before, according to Up for Growth data.

Even so, San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo said in July he supports banning single-family developments near commercial corridors and transportation hubs.

“Let’s face it — most of the Bay Area is still suburban,” Liccardo said in a panel with other city mayors at the time. “You got lots of family housing and you’re not going to bulldoze it to go build apartments, at least not if you don’t want them to burn down City Hall.”

Like Up for Growth, Liccardo doesn’t advocate for upzoning everywhere, but supports allowing the construction of “medium-density” buildings such as duplexes, triplexes or fourplexes in certain residential areas, especially around transit and job centers.

While some cities and states, including Minneapolis, Minnesota and the state of Oregon, have already made moves to overhaul and effectively upzone single-family areas to allow more duplexes and triplexes, the idea is still controversial, Kingsella said.

“That is really difficult to move those kinds of policies at the city council level because the constituents, it’s human nature, are reticent to change,” he said. “What Oregon did as the first in the nation as a legislature, taking this issue on and doing it at a statewide level really provided necessary cover to get that solution to scale in communities across that state.”

But even as Up for Growth advocates for cities to rethink their growth plans, Kingsella acknowledges there is no “silver bullet” to address the housing crisis, caused by a mix of longtime land use and tax policies, extraordinary job growth, an unprecedented long economic upturn and rising building costs, among other factors.

Other efforts around the Bay Area to push forward development are also part of the solution, including the major companies that have promised new grants, loans and land as part of a commitment to help spur the development of thousands of new homes in the region, Kingsella said.

Kaiser Permanente, for instance, was one of the first major companies this year to announce a housing and homelessness commitment as the Oakland-based health care giant with locations across the Bay Area aimed to improve health outcomes for its patients.

“From a systems perspective, we know that people who are unstably housed or are unsheltered live 27 years fewer than people who are stably housed,” Angela Jenkins, director of strategic initiatives at Kaiser Permanente said during the SVEDA panel. “We know that people who are unstably housed utilize … the system at three to four times higher rates than those who are stably housed.”

Kaiser also partnered with Bay Area Community Services and launched an initiative that focused on finding affordable housing for 515 homeless seniors in Oakland with a chronic health condition. The organizations achieved that goal quickly.

If further analysis of the initiative proves the effort was effective in achieving various goals, the company would likely consider expanding the program to other areas that Kaiser serves, Jenkins said in an interview after the panel.

In the meantime, Bay Area companies and public officials continue to work on various initiatives to address the housing shortage, and Newsom pushes to get 3.5 million homes built in a state where currently only 2.8 million are allowed to rise.

“It’s a market failure that limits economic mobility for low-income households and carries with it environmental costs, meaning that more cars are on the road,” Kingsella said. “Housing ultimately is at the intersection of community development and economic development and the broken housing ecosystem undermines the objectives of both of those areas of work.”

Contact Janice Bitters at [email protected] or follow @JaniceBitters on Twitter.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.