The water that inundated the neighborhoods surrounding Coyote Creek nearly three years ago has receded, but the residents of the area are still grappling with the devastating effects — three years later.

Friday marked three years since heavy rain caused a deluge that put hundreds of San Jose households underwater, displaced 14,000 people in three neighborhoods and left behind $100 million in damages. And meanwhile, a legal battle continues as 150 flood victims and their families are still fighting the governmental agencies that were supposed to warn and protect them for compensation.

Cat Lavelle, who lives on South 19th Street with her husband and three kids, remembers going for a run that morning and being aware the creek was rising. But it couldn’t possibly spill over the 30-foot banks, she told herself.

“Looking at it, you think it would take an unfathomable amount of water to rise that high,” Lavelle told San Jose Spotlight. “I didn’t really think it was a risk to me.”

She was wrong.

By late afternoon, Lavelle, 39, then five months pregnant with her now 2-year-old son Brendan, was frantically loading a laundry basket with diapers, clothes and toiletries, gathering essentials they would need once they evacuated to her in-laws’ house.

A helicopter flew overhead; a voice on a loudspeaker announced it was time to evacuate. Part of the reason she didn’t realize the situation’s gravity, she said, was the lack of notification until the eleventh hour. By the time the booming voice told her to leave the house, the water had already risen to her knees.

“There was no warning or information coming to us from the city or anything,” she said. “By time I pulled out of my driveway, the water had already crested over the gutters in the street.”

She texted her husband Brendan, a high school history teacher, at Stanford Hospital where he was visiting his mother who had been diagnosed with leukemia shortly before the flood.

When the family returned to their home a few days later, they saw the aftermath. The flood waters destroyed their finished basement and storage space. It ruined their camping gear, their TV, their photo albums and a cache of baby stuff — breast pumps, clothes, a baby swing.

But it wasn’t just the cost of replacing property and repairing their home that hit the Lavelles hard. It was the intangibles.

“It robbed us of time with my mother-in-law,” she said. “We weren’t able to give her the attention she deserved.”

At roughly 10 p.m. — when the family was at Lavelle’s in-laws’ house watching the events unfold on the news — a text message popped up on her phone. It told her it was time to evacuate.

The fight goes on

While those living in the flood zone are required to have flood insurance, Lavelle said that insurance only covered $20,000 of the nearly $50,000 in damage. Lavelle’s family is part of a lawsuit against the Santa Clara Valley Water District and the city of San Jose.

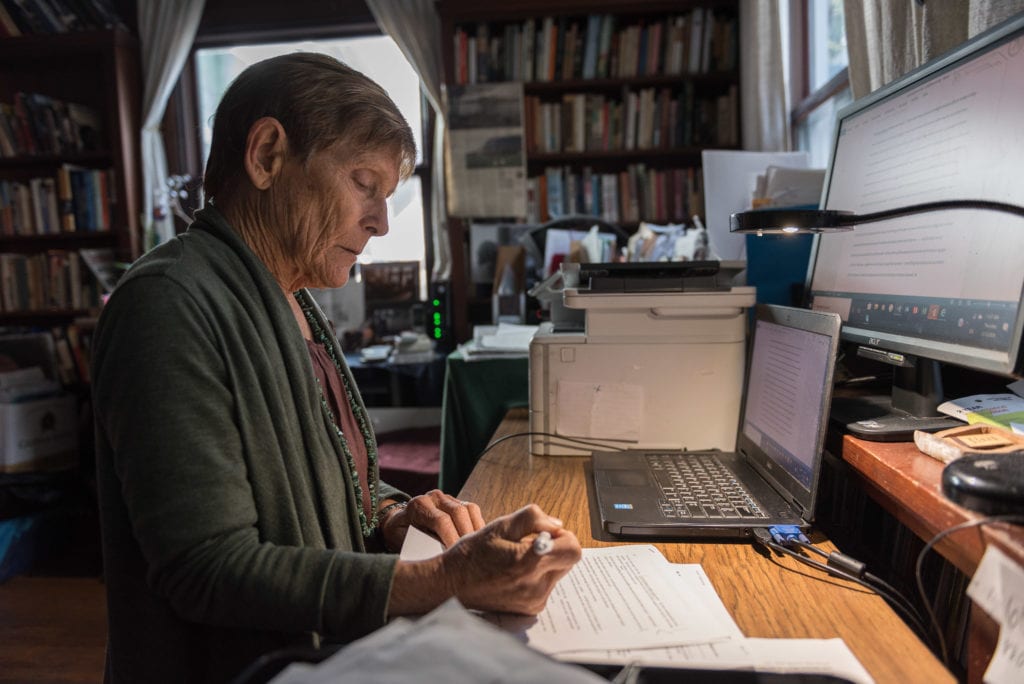

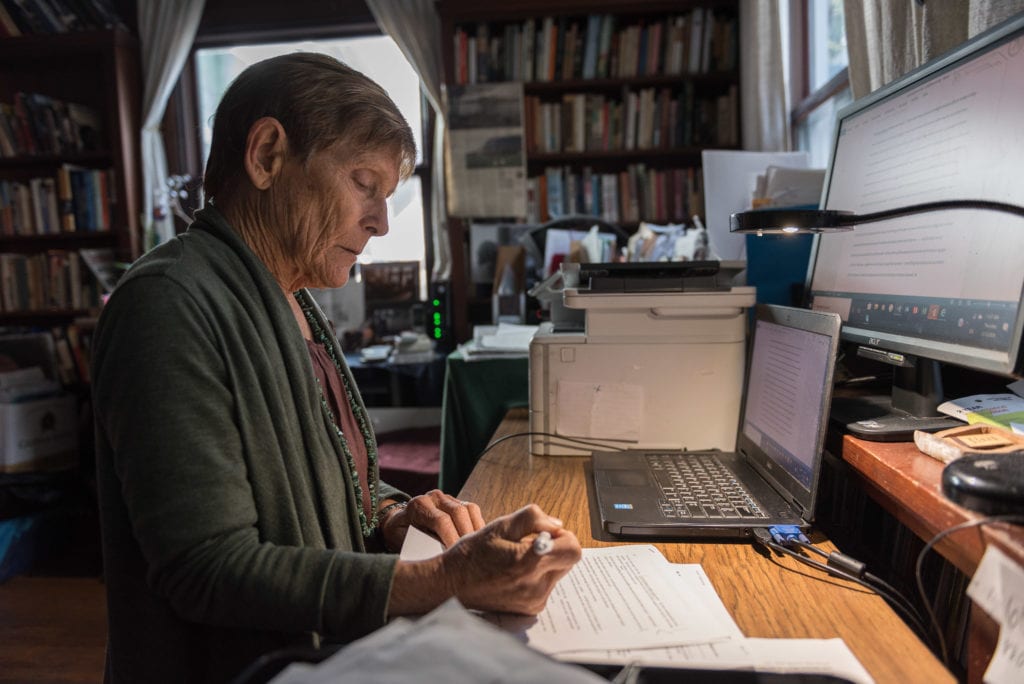

Amanda Hawes, a local attorney representing the flood victims, said, San Jose failed to have adequate emergency preparedness and that the Water District had not adequately invested in necessary infrastructure to mitigate the 100-year flood.

“Problems you don’t fix now will come back to bite you,” she said. “It shows up in the budget, but it doesn’t show up in reality.”

Hawes said the case has “a lot of moving parts” and said it’s still in the discovery phase. Depositions of public employees are expect to begin next month.

“What is it going to take so that nothing like this never ever happens again? A bureaucratic solution is just that. Time is running out… it needs to be a priority,” Hawes said. “We have to learn from history now and stop kicking it down the road.”

Matt Keller, a spokesman for the water district, declined comment.

However, he wrote in an email, Valley Water installed an interim flood wall in December 2017 and continues to move forward with its Coyote Creek Flood Protection Plan. That plan’s objective is “to reduce the risk of flooding to homes, schools, businesses and highways in the Coyote Creek floodplain for floods up to the level of flooding that occurred in 2017.”

Valley Water also offered flood victims a $5,000 non-negotiable payout, according to Valley Water documents. But acceptance of that payout required the roughly 200 victims to sign a release forfeiting their ability to sue for further damages.

Meanwhile, victims such as Lavelle are still waiting to be reimbursed for damages three years later.

City makes changes to its system

Roberto Araujo, 52, another victim named in the lawsuit, said the flood forced his daughter Anna, then 18, to drop out of cosmetology school so she could work to help support the family. The flood ruined the family’s two cars and numerous personal items.

“It took so many years to get good stuff, and it was all lost in one day,” Araujo said. “Recovering is the hard part, to lose all those pictures, those memories.”

His wife still cries over those lost memories, he said.

“I am frustrated,” he said. “The city, the water district — they were supposed to come back to see the damage but they never came back. People forgot.”

An audit conducted by Witt O’Brien’s, a DC-based crisis and emergency management firm, shows that San Jose accepted responsibility for its lack of preparedness and failure to invest in preparedness or response and recovery initiatives.

A month after the Coyote Creek flood, San Jose hired Ray Riordan as its director of emergency management. He said there have been “significant changes” made since then, including a Joint Emergency Action Plan, which better coordinates emergency management communication between Valley Water, the city and the county.

A new emergency alert system, available in multiple languages, allows rapid response to a disaster in multiple languages. The city used the system, called Santa Clara County Alert, the summer following the flood to inform residents about a heat wave. It has also rekindled its Certified Emergency Response Team training, a program that equips citizens with skills to aid in a disaster, Riordan said.

‘Someone in power did not advocate for us’

But such measures are cold comfort to victims like Teresa Pedrizco.

Pedrizco, 43, had to retake the bar exam because of the flood. The delay meant her moral character application — where the state, among other things, conducts a background check — expired. Although she has since passed the bar, Pedrizco still cannot practice law because her new application has yet to clear.

The flood also damaged the foundation of her 21st Street home in San Jose. She managed to buy sandbags before the flood but said no one showed her how to use them.

“Watching the evening news, that is when it sunk in that the city knew. I thought, ‘Wait a minute — they knew,’ so I started to be angry,” she said. “Until this day, that feeling of anger doesn’t disappear,” she said.

The insurance adjuster estimated the damage to Pedrizco’s foundation to be less than $5,000, but she couldn’t find anyone to do the work for that amount of money.

Then Pedrizco’s cracked foundation caused her house to sag. City code enforcement officials said she’d be fined if she didn’t fix it, and the actual costs to repair the flood damage is estimated to be between $200,000 and $280,000, she said.

“We elect these people to represent us, to look after the interest of the residents,” she said, “and realizing that someone in power did not advocate for us, did not use their common sense to say, ‘Hey we need to let them know.’ That is very irritating.”

Contact David Alexander at [email protected].

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.